The new Hepatitis C virus (HCV) drugs are a major medical breakthrough. Over three million Americans are being promised a cure to an otherwise chronic disease. If left untreated, HCV can cause cirrhosis (scarring of the liver) leading to serious consequences, including liver cancer. Old treatments were not effective and had many debilitating side effects. A better regimen has been demanded for years. Enter Gilead Pharmaceuticals with their wonder drug Sovaldi, touting over a 90 percent cure rate with minimal side effects. However, there’s a catch, and an expensive one at that.

In the U.S., Sovaldi initially retailed at $84,000 per patient for the standard 12 weeks of treatment, or $1,000 per pill. In France, the same drug was sold at the discounted price of $51,400 (40 percent less than the U.S. price). This stark over-pricing in the U.S. has limited patient access, threatened government financing, and fueled frustrations over drug pricing policies.

Pharmaceutical companies like Gilead are businesses. Their high prices—enabled in part by generous patent regulations—produce large margins of profit. These earnings remain a strong incentive to the discovery of life-saving medicines. Still, the industry claims these profits are necessary to make up for their expensive investment in research and development, which can take many years and billions of dollars.

Here’s what’s troubling. In 2011, Gilead spent $11 billion to acquire Pharmasset, which developed the new HCV drugs, and as of February 2015, they have already recouped $12 billion in sales. In the long run, they stand to earn over $200 billion worldwide. Overpricing is clearly driving exorbitant profits.

Gilead has defended its high prices by asserting that they “reflect the value of the medicine.†A 2011 study from the Center of Disease Analysis supports this notion, estimating the average lifetime healthcare cost of a patient living with HCV was $64,900. In Europe, prices reflect this value, with the average cost of Sovaldi ranging from $50,000 to $60,000. Although U.S. retail prices are significantly higher, market forces appear to be pushing prices down closer to this “medical value.†Competition is driving price cuts, as Gilead and their challenger, Abbvie (which is marketing Sovaldi competitor Vierpak) duke it out.

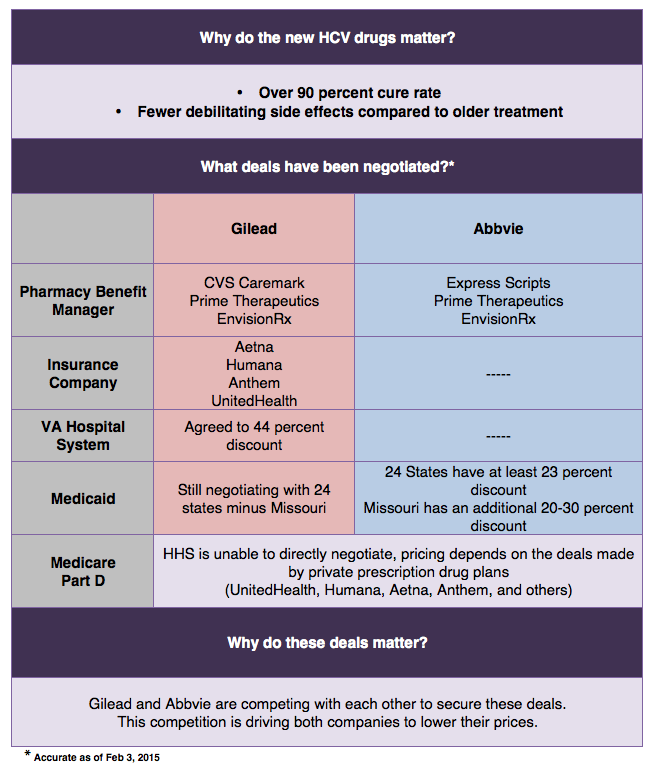

Both companies are providing discounts in exchange for exclusivity on the formularies, or approved drug lists, of insurance plans. Abbvie dealt the initial blow by signing a deal with Express Scripts, offering an undisclosed discount. Gilead has since countered by winning a majority of the market share by signing deals with Aetna, Anthem, Humana, UnitedHealth and CVS Caremark. Recently, Gilead promised a 46 percent markdown, representing a step in the right direction, but this still may not go far enough to ensure access for HCV patients.

Private insurers are visibly having trouble negotiating lower prices; a better mediator is needed. Enter, government programs. Veterans Affairs (VA) cut a deal with Gilead last year for a 41 percent cut (to $50,000). This year they will receive an over 50 percent discount (to $42,000). A similar trend is occurring in Medicaid. A group of 25 states are in negotiations with Abbive, and so far Missouri secured a 50 percent discount ($41,000); the pressure is now on Gilead to counter.

Yet even these price reductions do not make the drug more accessible for patients. In the VA, budgetary constraints have limited treatment to only 8,500 of 175,000 patients. An additional 30,000 may receive the new medications pending Congressional approval of an extra $1.3 billion for HCV drugs alone. Medicaid has set up restrictions, requiring patients be drug and alcohol free for 1 year before receiving treatment. These restrictions are effective; in Illinois, 43 of 50 Medicaid patients requesting the drug were denied in the month of October.

The VA and Medicaid simply cannot afford to cover all HCV patients even with half-price discounts, leaving many patients simply waiting to get sicker to qualify, which will eventually cost the system even more. A better solution must be found. Perhaps a stronger governmental program with more political influence could lead more successful price negotiations. Medicare Part D may be the answer.

Medicare Part D funds prescription drug plans for citizens over 65, funded by a payroll tax and managed by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Part D holds numerous negotiating advantages over other government programs. For example, it avoids the state-by-state fragmentation of Medicaid, and has a massive patient pool compared to the VA. Wielding such clout, HHS (representing Medicare Part D) is the ideal choice to lead price negotiations.

Unfortunately, negotiations between HHS and pharmaceutical companies are illegal. During the passage of Medicare Part D in 2003, the pharmaceutical industry successfully lobbied for a “non-interference clause,†which prohibits the HHS Secretary from engaging in such negotiations. In 2009 the industry demanded Congress maintain this clause in return for their support of the Affordable Care Act, a deal Democrats could not pass up.

A bill titled “Medicare Prescription Drug Price Negotiation Act of 2015,†introduced by Senator Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), is currently under review by the Senate Finance Committee. If enacted, the law will give HHS Secretary Sylvia Mathews Burwell the option to take on companies like Gilead. However, the bill’s chances of success are abysmal. Identical bills have died in Congress 10 times since 2003. Govtrack predicts a 1 percent chance of it passing the committee. Only a small glimmer of hope remains with the recent presidential budget for fiscal year 2016 supporting direct negotiations.

For now, patient access is limited, policy solutions are unrealistic, and Gilead’s profits are boundless.

Sumit R. Kumar is an M.D., M.P.A. candidate at NYU. He is pursuing a career in Internal Medicine. Follow Sumit on Twitter. The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of NYU or any other entity.